If the tiny Indonesian island of Komodo is known for anything other than the Komodo dragon, it is for the characteristic harsh conditions that prevail there. Had it not been for these conditions, human influx would have reduced the Komodo dragon habitat to a concrete jungle long ago.

In 1927, when the Reptile House at London Zoo opened, all eyes were on the two Komodo dragons that were brought there from their native habitat in the far east. The Europeans got to see something that they had never dreamed of – a lizard species, which was bigger than the average adult human. The existence of these lizards was not known until the Europeans bumped into them in 1910, but thanks to the numerous studies carried out over the last hundred years, today we are aware of some of the most fascinating attributes of their life–their habitat being one of them.

The Komodo dragon or Komodo monitor (Varanus komodoensis) is the largest of the 5600 odd living species of lizards. A member of the monitor lizard family, the Komodo dragon is known for its enormous size; attaining a length of around 6-10 feet and weighing somewhere between 140-160 lbs at full growth. The gigantic size, clubbed with their serrated teeth and sharp claws, helps them dominate their natural habitat, taking down and feeding on anything that they come across; carrion, snakes, and fellow dragons included.

When the Europeans did get to see the species — the two Komodo dragons which were exhibited at the London Zoo in 1927 — they were left dumbfounded. In fact, the whole world was, when they learned about the existence of a lizard species found on some never-heard-of islands in the Indian Ocean that was even bigger than the humans.

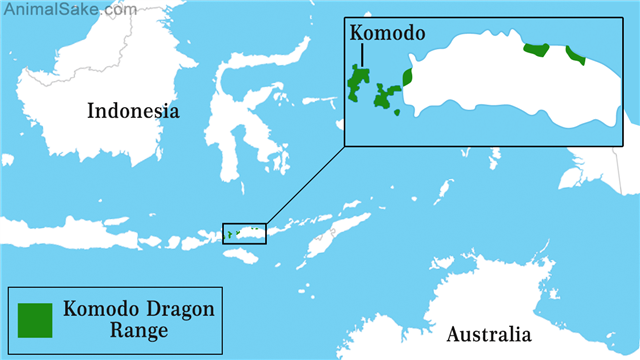

Where are Komodo Dragons Found?

If the existence of Komodo dragons was not known until 1910, it was because of their restricted habitat. The species is only found on some remote islands of the Indonesian archipelago, like Komodo, Flores, Gili Motang, Rinca, and Padar — the ‘never-heard-of’ islands, which are geographically a part of Asia. Their former range spanned the whole of Flores and several other tiny islands in the vicinity, from where they seem to have disappeared all of sudden.

Though the species inhabited a couple of islands of the Indonesian archipelago, it was primarily found on the island of Komodo — hence the name. The species was named by American adventurer, W. Douglas Burden when he lead an American expedition to Komodo in 1928.

Komodo Dragon Habitat – Salient Features

Komodo dragons inhabit the arid volcanic islands in the Indian Ocean. With the normal temperature on these islands typically exceeding 80 °Fahrenheit, the region is considered one of the harshest places on the planet. These islands face a severe scarcity of water as it only rains here for about a month or so in December. The region virtually goes dry between March and November, and that’s where their ability of surviving without water for a long period comes into the picture.

When the temperature becomes unbearable, these dragons dig burrows using their sharp claws and take shelter. When the temperature falls, the cold-blooded creatures are seen basking in the sun all over these islands. Being a diurnal species, the Komodo dragons are most often seen active during the day. They do step out in search of food at night, but such instances are very rare.

Other than water shortage for most part of the year, the species also has to tackle frequent volcanic eruptions, soaring temperature, and cannibalistic behavior of fellow individuals (in times of food scarcity). And even though the monsoons do hit the island chain for a very short period, even that causes the islands to flood and adds to their woes.

How the Habitat Affects their Diet and Behavior

Komodo dragons feed on water buffaloes, deer, wild boars, snakes, and other small animals found in their natural habitat. While they prefer hunting deer and small mammals, they can also bring down large animals, like a full-grown water buffalo, by hunting in groups. Otherwise a solitary species, the Komodo dragons are only seen in groups when they are hunting or feeding. Being the lone apex predator in this region, the species seldom experiences food shortage. If at all they do, they either resort to carrion, or go to the extent of hunting their own kind.

In addition to their sharp claws and serrated teeth, these lizards are also armed with toxic saliva that can kill their prey within a few hours; that’s ‘if’ it succeeds in surviving the brutal assault in the first place. These reptiles can sprint for short distances notching speeds of up to 15 miles per hour, which comes handy when hunting in a region which is more or less a barren land. Other than that, they can also climb trees, dive, and swim. In fact, the young ones spend the first few years of their life on the trees, avoiding adults of their own kind that are known to prey on them.

The arid habitat of the Komodo dragon is unsuitable for human habitation and that’s the only reason that the species has been able to survive human onslaught till date. But for how long they will be able to stay off the human radar is difficult to say. Poaching and loss of habitat have already started showing its effects on the Komodo dragon population. The species has been enlisted as a ‘Vulnerable’ species in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Now it is up to the administration to ensure that they continue to flourish on ‘their’ islands.

Worth a thought: Like we said, Komodo dragons are restricted to a few volcanic islands. What ‘if’ some underwater volcanic activity joins these islands with the remaining islands of the Indonesian archipelago? The chances of this cannot be ruled out. (The American continents were subjected to similar occurrence when the volcanic Isthmus of Panama surfaced.) If it does happen, it will give a free-hand for the Komodo dragons and spell disaster for the other species. This can be simply dismissed as an irrational hypothesis, but a closer look, and you will realize that it is definitely worth giving a thought to.