The coast of the Pacific, especially to the east and north, is home to the magnificent sea otter. This marine mammal can live on land with the same ease as it can live in the water without surfacing for days. The life cycle and habitat of the sea otter are just as fascinating as the mammal itself.

Sea otters inhabit the shorelines that span across Alaska and Japan. These beautiful creatures display an interesting social behavior that includes the following.

- Caring for orphaned juveniles

- Matriarchal feeding trends

- Delayed Implantation

Habitat and Distribution

Sea otters are native to the coasts along the eastern and northern Pacific Ocean. They prefer the shoreline to the deeper waters. They thrive in warm, coastal waters and usually remain within a kilometer from the shore. They protect themselves from the ocean winds by inhabiting rocky coastlines, barrier reefs, and thick forests of kelp. They choose areas that have rocky substrates. Currently, the species has stable populations in Alaska, along the Russian east coast, Washington, British Columbia, and California. They have also been sighted in Japan and Mexico. In Russia, sea otters thrive along the Kuril, Kamchatka, and Commander Islands.

Diet

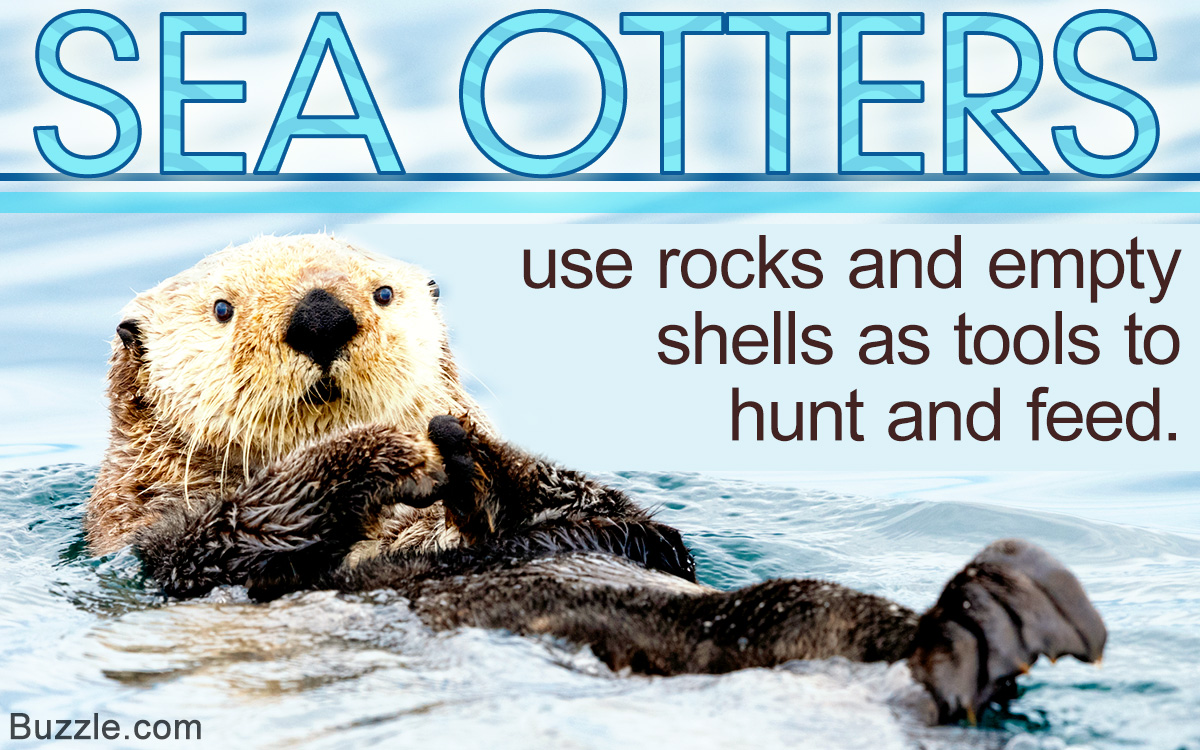

Sea otters consume a diet that is derived from a wide range of resources. They feed extensively on marine invertebrates like sea urchins, bivalves, mussels, clams, abalone, mollusks, snails, and crustaceans. They also consume limpet crabs, pismo clams, and giant octopuses. They eat large quantities of fish and kelp. They add to the quality of kelp forests by keeping the animals that graze on kelp at bay. They differ in foraging methods and food preference between populations. The matriarchal dwellings witness a trend where all the members follow the mother’s eating habits. Some even eat large sea urchins.

Life Cycle

Sea otter males mate with multiple female partners. The bonding between a pair, while the female is in estrus, is temporary. They mate in water and the males are known to be quite rough on the females. They sometimes bite the female’s muzzle, scarring the nose, and have even been observed to dunk the female under water, not allowing her to surface for a long time.

Maximum births occur between May and June each year, among the northern populations. Among the populations in the south, the peak period is between January and March. The gestation period can be anywhere between four and twelve months. A unique feature of the sea otter is that the females can actually delay implantation, which is then followed by four or five months of pregnancy. Sea otters can breed twice a year.

Most females produce a single pup. The pup weighs between 1.5 and 2.5 kg. There are instances of twins, but they are rare. However, it has been observed that in the case of twins, only one pup survives. Pups are born with their eyes open and a fine set of teeth. The thick coat of fur is groomed by the mother, with consistent licking and fluffing. In about 12 weeks, the baby fur is shed and adult fur is flaunted by the youngster.

The mother nurses the pup for six to eight months and introduces the little one to bits of prey thereafter. She teaches the pup to swim and retrieve food. Juveniles become independent by the time they reach eight months of age. There have been instances when the mother abandons a pup while dealing with a scarcity of food. The onus is on the females to feed and raise the juveniles. They may even take in orphaned pups.

Female sea otters become sexually mature at four years, while the males take a month more; however, breeding takes place much later. In the open, natural habitat, sea otters live up to a good 23 years, while in captivity, they survive up to 20 years.